‘Reshaping Cultural Connections in a Globalized World’

Decolonized approach to identity can resist exploitation of values and foster unity: Dr Bargallie

The individual and collective identity defines the nature and characteristics of a person and a society. Identity is shaped by relationships, histories, and evolving contexts and is vital for mental peace and civilizational development. In a globalized world where societies are increasingly multicultural, adopting a relational and decolonized approach to identity can bridge divides, foster inclusivity, and reshape cultural connections. This perspective not only promotes a more equitable and interconnected future but also resists the exploitation of values, focusing instead on the shared humanity that unites us all.

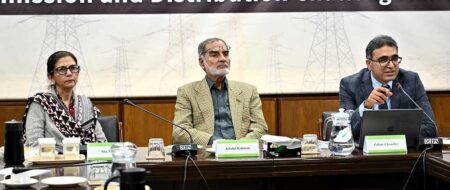

This was noted by Dr Debbie Bargallie, associate professor and principal research fellow at Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research and Griffith Institute for Educational Research, Griffith University, Australia. She was delivering a talk during a seminar on ‘Reshaping Cultural Connections in a Globalized World’ at IPS on November 19, 2024. The session was chaired by Dr Khalid Masud, member, Shariat Appellate Bench, Supreme Court of Pakistan, and joined by Khalid Rahman, chairman IPS.

The event served as a precursor to an international seminar titled ‘The Role of Religions in Fostering Peace, Harmony, and Justice’, which IPS was set to hold on December 4.

Dr Bargallie highlighted the interconnectedness of cultural histories and identities, emphasizing how relationality and positionality shape knowledge and social research. Drawing from cultural theorist Stuart Hall’s concept that all narratives are “in context” and positioned, she called for revisiting sidelined histories to foster a more inclusive understanding of cultural connections and identities.

She shared insight from her research and personal experiences, exploring the historical links between Australia, Islam, and cultural relations. She noted that trade and cultural exchanges between Muslims and Aboriginal Australians were established long before European colonization, as evidenced by ancient maps by Al-Khwarizmi drawn in 820 AD and Kilwa Sultanate coins found in Australia. These artifacts reveal a period of mutual engagement that predates European settlement.

Dr Bargallie also elaborated on the contributions of 19th-century Muslim immigrants, including Afghans, Indians, Algerians, and Malays, who shaped Australia’s industries as cameleers, farmers, and hawkers. These contributions underscore the early foundations of Australia’s multicultural fabric. However, she noted the challenges faced by these communities under the racially exclusionary White Australia policy, which marginalized non-European migrants. Sharing a personal connection, she recounted how her great-grandfather, a Muslim from Punjab who migrated in the 1890s, was unable to leave Australia due to discriminatory policies like the English dictation test.

Despite such challenges, the resilience and growth of Australia’s Muslim community have significantly enriched the nation’s multicultural identity. Pakistani migrants, now the 17th largest migrant group in Australia, exemplify this vibrancy. Moreover, Islam, as the fastest-growing religion in the country, now accounts for 3.2% of the population, highlighting the increasing acceptance of cultural diversity.

She noted that these histories and relations are never depicted in mainstream literature and discourse due to the adoption of Eurocentric approaches. She called for a decolonized approach to cultural studies that values indigenous epistemologies, marginalized voices, and non-Eurocentric frameworks. She advocated for narratives that emphasize shared histories, fluid identities, and relationality to address systemic challenges like displacement, marginalization, and loss of cultural heritage.

Dr Bargallie said that within this decolonized approach, national frameworks rooted in inclusivity could serve as powerful tools for promoting harmony and coexistence under a shared identity. Such an approach has the potential to transform civilizational relations, fostering mutual respect, tolerance, and progress while paving the way for a united and forward-looking community.

In his concluding remarks, Dr Khalid Masud reflected on the evolving nature of identity in a globalized world, emphasizing its dual potential to unify and divide. He noted how political identity, often replacing religious identity, has become a source of exclusion and conflict in many countries. Unlike political identity, which imposes boundaries, cultural identity offers a more inclusive and expansive sense of belonging.

He stressed that, in the digital era, where identities are increasingly shaped and politicized, there is a need to resist the exploitation of values and instead focus on the shared humanity that connects us all. As nation-states diminish in significance, cultures emerge as the foundation of identity, offering a path toward reimagining humanity and fostering a more inclusive and interconnected future.