The Border as Strategy The Case of Afghans in Peshawar

The protracted structural crisis of Afghanistan has caused one of the most important and lasting outflow of refugees in the world and Pakistan, which bears the bulk of the refugees with Iran, is in need of a long-term vision to deal with such burden

Policy Perspectives, Vlm 4, No.1

Abstract

[The protracted structural crisis of Afghanistan has caused one of the most important and lasting outflow of refugees in the world and Pakistan, which bears the bulk of the refugees with Iran, is in need of a long-term vision to deal with such burden. This paper proposes to look for answers in the strategies deployed by Afghans living in Peshawar. It shows how these strategies relate to longstanding historical patterns of trade and migration in the region and how they have been modified by the history of the Pak-Afghan border. It argues for a borderland perspective in studying the evolution of this relation between the Pashtun tribes of Southern Afghanistan, the state, and its borders, to see how this evolution has shaped the current crisis as well as the strategies for coping.

Empirical research for this paper has been carried out entirely in Peshawar for its relevance to the study. It is the main urban center of the North West Frontier Province (NWFP) of Pakistan, and host to the highest concentration of refugees (20 percent of all Afghan refugees residing in Pakistan). It houses main offices of a number of trading and transport companies, thus making it an extension of the border heartland. Afghans and tribal entrepreneurs and traders operating from the city have been interviewed, in addition to informed scholars and professionals working and living in the city, as well as in Islamabad.[1] The focus of the research was on qualitative data about notable Afghan economic niches in Peshawar, namely in the trucking business, carpet trade, and the Karkhano market. – Author]

Introduction

In March 2005, UNHCR and the government of Pakistan realized their Census of Afghans in Pakistan. The exercise aimed at counting all Afghans living in Pakistan since 1979, thus going beyond the limits of refugee camps. The results provided new insight into the scope of the task ahead, the changing nature of the issue and important data for better understanding the phenomenon. Among the important points, the census confirmed certain changing patterns of integration and “sedentarization” into Pakistani society. This shows that most Afghans do not foresee the possibility of any short-term improvement in the situation of Afghanistan. Part of the challenge is thus to understand the deep-seated structural issues leading to the length of the crisis. To achieve this, it is crucial to understand how the Afghans themselves have responded to the crisis.

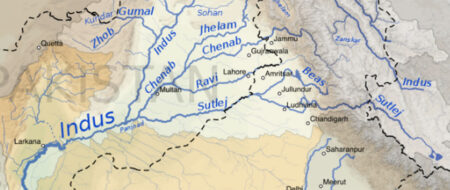

According to the census, more than 85 percent of 3,049,268 Afghans live in the North-West Frontier Province (62 percent) and Balochistan (25 percent), 20 percent in the Peshawar district alone.[2] This is not fortuitous. Geography — these two provinces form Pakistan’s entire border with Afghanistan and more than half of the refugees also come from provinces directly connected to the border — community of language and custom explain this choice.[3] In addition to culture, also comes the question of traditional livelihood, age-old migratory patterns, and historical relation between both host and refugee populations to their respective state. In short, NWFP is more than just a host region; the whole of the Pashtun tribal belt, shared between Afghanistan and Pakistan is a homeland of its own, with its own organic national culture and history, made of wars, territorial contention, migration patterns, trade and traffic, and resistance against foreign powers — not the least, against the very states that claim control on either side. NWFP, and particularly the adjacent Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), share with the east and southeast of Afghanistan, a common and deeply interconnected tribal culture. And for them the border has become more than a mere dividing line. It has become a way of life.

This study aims at understanding this peculiar borderland “ecosystem,” of looking at it from the periphery, that is, by taking the frontier area not as the limit, but as the territory itself, and the border as the central function of this area. In this borderland, Afghans are not merely refuge seekers. They — along with the tribal Pashtuns from the Pakistani side — have developed intricate coping and profit systems of the cross-border economies, putting the advantages (and disadvantages) of both sides to profit. The case of Peshawar will provide us with the ideal microcosm for the study. As the region’s main urban center and for its privileged access to the border, Peshawar is also the center of a thriving cross-border economy with, at its heart, a powerful transport industry, articulating a well developed Pak-Afghan import-export network, as well as one of the most important smuggling and drug network in the world.

Pakistan: The Afghan Presence in Context

Nearly three decades of incessant wars in Afghanistan have created the single largest and one of the most lasting movements of forced migration in the world today. This massive population movement has neither been uniform nor unidirectional. It is marked by the back and forth movements between Afghanistan and Pakistan as the conflict seemed near resolution, reignited or mutated. Indeed, since 1979, the conflict has metamorphosed continuously as the resolution of each chapter led to the surfacing of more dissentions and dispute.

Afghans have been living in Pakistan for 27 years now. Many of the younger generation have never even seen Afghanistan. A clear majority (58 percent) lives outside the camps, which signifies that they themselves have since long begun to look after themselves and for long-term strategies inside Pakistan. In addition to the ongoing fighting and economic insecurity in Afghanistan, the waning support by foreign donors and the progressive closing of camps have in the long run favored their entrenchment deeper in Pakistani society, forcing them to develop their own coping strategies, rather than encouraging them to go back. As policymakers begin emitting contradictory signals towards the refugees, reliance on official instances also withers away and the trust developed among the actors of informal and traditional social networks takes an increasingly important role.[4]

Theoretical and Practical Challenges to the Refugee Approach

The traditional refugee framework in use presents a number of problems in the context of the Afghan crisis, to which there exists no facile solution. Defining who is a refugee is itself a challenge in the context. In legal terms the status of the Afghans remaining in Pakistan is ambiguous. By international law, economic migrants are not entitled to refugee status and are clearly excluded from the 1951 UN Convention Relating to Status of Refugee as well as from the 1967 protocol.[5] However, in complex cases like that of Afghanistan, where economic and security rationales are so intricately interwoven, there is need to question this categorization.

Refugeedom also heavily overlaps with other forms of cross-border movements, like seasonal migration, nomadism and transnational tribal links, such as intermarriages, etc. These movements have been going on for centuries, even millennia. Traditional custom livelihood, economic strategies intertwine and security has added a new motif into the rationale and way in which these migrations take place. There is still great fluidity of cross-border movement despite the officially tightened security. The Pashtun tribal people from FATA, who are not subject to complete Pakistani sovereignty[6] have conserved their relations with their relatives on the other side of the Durand Line. Cross-border intermarriages, for example, are quite frequent among mountain tribal people and have probably increased with the war, as a way of reducing risk — physical and economic — and strengthening political alliances and trade partnerships.

Another great practical challenge posed by the Afghan refugee phenomenon is its endurance in time. As shown by the high numbers living outside the camps, they acquired economic significance in Pakistani society, particularly in Peshawar; they have long since begun to integrate and normalize their life in the host country. Peshawar, of course, has been an ideal environment for this. Not only is it the closest urban center to the Afghan border: its culture, language and lifestyle are not fundamentally different from those of Afghanistan. Patterns of “normalization” were beginning to appear already in the 1980s, as tents were replaced by mud houses.[7] As legal limitations outside the camps were quasi null, Afghans could easily exploit social networks to arrange for shelter, work and business. With time, new networks among Afghans, or between Afghans and Pakistanis, have developed and strengthened, and new economic patterns have created a particular Pak-Afghan “ecosystem.”

The Afghan refugee problem illustrates very well one of the crucial challenges posed by conflicts in the post-colonial world. Conflict, as traditionally seen, is an interruption of peace, and consequent emergencies to be resolved naturally by the ending of conflict and reconstruction of damaged infrastructure: in other words, return to normalcy. This vision unfortunately comes short of dealing with such situations as in Afghanistan, where it is the conditions of “normalcy” themselves which, in Afghanistan are at the source of the enduring instability.[8] In the post-colonial world, political instability inherited from artificial boundaries and political fragmentation, intertwines intricately with economic vulnerability, endlessly engendering one another. In Afghanistan today, a premature return of refugees on the claim that economic rationale is not a valid motif for refugeedom, may be oil on the fire of an ongoing humanitarian crisis. The added pressure of hundreds of thousands in need of rehabilitation risks increasing vulnerability and fuelling more instability, pushing back new waves of asylum seekers.

Vulnerability in Afghanistan also translates in another vicious circle, where the lack of livelihood possibilities leads the impoverished to turn to smuggling or poppy cultivation as a way of survival. Thus, these high-profit activities sit at the intersection of coping, shadow and war economies, empowering local militias, profiteers as well as the Taliban, ensuring more rounds of warfare.[9]

The Political Economy of the Tribal Belt: A Borderland Perspective

The current refugee situation in Pakistan, particularly in NWFP, is set on the fault lines of post-colonial state consolidation. It is the result of a complex crisis in the international order which, at the local level has produced a similarly intricate borderland crisis, with deep international, even global repercussions.[10]

Ironically, the British-designed border separating Pakistan and Afghanistan has been the one that cemented their mutual historical fate. Splitting the Pashtun belt in two, it has led to a reconfiguration of certain inter- and intra-tribal relations, nomadic movements and trade practices, but has never succeeded in creating completely distinct communities. Social and economic networks of the borderland tribes have rather been reshaped directly in function of the border. With the introduction of the border, the tribes straddling the line were put in a privileged position for smuggling, and the 1959 Afghan Transit Trade Agreement inaugurated an era of unprecedented traffic further amplified with the refugee crisis, even becoming the dominant source of income among certain tribes.[11] Thus, the Durand line created a borderland ecosystem of its own. Yet this dissident borderland cannot be termed independent from either states. Their position indeed makes them extremely vulnerable to the national and international political dynamics. What we observe could rather be described as subversive interdependence.

The refugee crisis, thus, has not introduced a completely new transboundary phenomenon, but it has intensified the already strong interdependence of peoples living on both sides of the Pak-Afghan border. By appropriating cross-border transport and trade, smuggling, drug and cash transactions, they succeeded in subverting the border itself into an instrument of negotiation for relative autonomy or access to state resources from either side.[12] War has, however, profoundly changed the borderland dynamics, creating immense pressure on age-old nomadic ways of life. Because of the deteriorating situation, many of them have since then settled in Pakistan after the erosion of their assets and the limitations war has put on their freedom of movement.

The refugee crisis thus gave a new shape, and a new importance to cross-border linkages, integrating the region further. These linkages go from formal business, such as transnational entrepreneurship, mostly in trade and transport; to shadow economy: smuggling, cash and credit business (hawalah), petty aid ‘recycling,’ drugs and arms trafficking; and then dive further in conflict economy, channeling funds from the black economy.

One of the most striking things about Peshawar and its surroundings is the omnipresence of Afghans in almost all sectors of (private) economic activities. And they have become, in most of them, unequalled. They are lauded (and resented) as hard and undemanding workers and have outclassed (and outpriced) the local wage laborer. In commerce of whatever scale, they are recognized as shrewd businessmen. Finally, they are very much present on the city’s money markets, as well as in the notorious smuggler’s markets of Bara bazaar and Karkhano. Obviously they are also perceived by the local population as the main drivers of black economy, arms and drug traffic. But as we will see, the inroads of these activities are relatively complex and involve more than one sector of activities, as well as more than one segment of the population. But the effects of the Afghan presence in these cannot be denied.

It will not be a surprise that the particular strength of the Afghan traders and transport entrepreneurs reside in their extensive social networks into Afghanistan. These networks, and often the border itself, represent unmatched assets for these Afghans allowing them unique cost-cutting and resource maximizing schemes.

Trucking Business: There is no general rule as to how transport companies -small or large- are organized concerning logistics, employment policy, ownership or hierarchy. Also, ownership is not homogeneous and a substantial portion of the medium and large size transport companies of Peshawar are also owned by Pakistanis, most often tribal people from FATA. Companies are organized around a family nucleus at the top, and then hire its lower rank employees from a competitive labour market, regardless of the origin. However the quasi totality of truck drivers is of Afghan origin and the vehicles are registered in Afghanistan. As most respondents to this research argued, Afghan truckers know the roads; they know the local power holders and are harder workers. The trucks, usually the more reliable and tougher Mercedes, are more suited for the difficult Afghan roads, as compared to the Japanese vehicles imported to Pakistan. And these, can only be acquired on the free markets of Afghanistan.

Most agencies dealing with Transit Trade (ATTA) comprise a core team dispatching between two up to a dozen vehicles on the road. Ownership patterns vary among these agencies, some acting mainly as middlemen for truckers owning their own vehicles. These go regularly to Peshawar to get their load and go straight to Afghanistan. Some truckers also work alone this way, owning their own vehicles. All vehicles are purchased and registered in Afghanistan. Also the Afghan truckers differ in their place of residence. Certain respondents (to the questions in interview) living in Afghanistan come to Peshawar only for loading. Others, though too having their trucks registered in Afghanistan, reside in Peshawar or in the area around.

Companies dealing with Pak-Afghan export trade are based on a system of warehouses, set in Peshawar and across the border. They receive regular input of commodities; rice, wheat, cooking oil, garment, cement, electric and electronic appliances, etc. that they keep in storage in Peshawar and send to Afghanistan when a critical mass is reached. Goods are then kept in a second warehouse on the way to Jalalabad, where the Afghan “branch staff” redirects it to the company’s clients in Kabul. These “branch offices,” run by relatives of the traders are left independently in charge of contacting and dealing with the clients. The companies thus maximize their proximity positions on both the sides, one harboring the central organization and financial decision-making in Pakistan where supply of commodities and access to financial resources is available; the other reaching out to clients, being at the proximity of the targeted market. But in the end, the gains remain within the clan.

General Trade: Considering traditional Afghan occupations, it will not be surprising to see Afghans be prominent in Peshawar’s bazaar economy. Afghans merchants and shopkeepers in Peshawar have taken considerable space in the local markets. They are everywhere in the cloth markets of Gora and Bara Bazaar. This is probably due to, in many cases, the individuals’ previous status as traders before arriving in Peshawar, thus profiting from their organizational skills and established networks. Many shops are also family shops established in Pakistan, which have grown, and of which the grown up children have inherited.

Money Exchange: The currency business (saraf, hawalah) is also a vital part of Peshawar’s markets, attesting of its emergence “as a hub of cross-border trade.”[13] A substantial number of the countless sarafis sitting around Yadgar Chowk are Afghans. Sarafis also act as hawalah (or hundi) agents, that is, as money transfer service providers. The hawalah system is of disarming simplicity. It works basically as a transfer of debt. A client who wishes to transfer a given amount of money goes to a hawaladar and gives him the amount he wishes to send abroad in cash. The hawaladar produces a letter of change, or as it is more common today, will make a phone call to a colleague where the money must be sent, who in turn will deliver the money in cash. The two dealers then will arrange the debt between them, either through the formal bank system or through deals in commodities.[14] This latter method of dealing in commodities also allows money dealers to diversify their portfolio and increase profits.[15]

The hawalah system also represents not only the greater integration of Afghan, Pakistani and international money markets, but also their growing interdependence, meaning that the position of each site plays a very specific role in this borderland system. Indeed, for dealers in Afghanistan, the money market in Peshawar — as that of Quetta — is vital for access to the international market, for funds to be sent to or received from abroad, and for access to fresh currency.[16]

Since the hawalah system is an informal system, it must also rely extensively on trust among stakeholders. It relies, therefore, extensively on kinship or other strongly established social networks across the border and abroad. As a matter of fact, in most domains of trade in the Pak-Afghan borderland — without reliable law-enforcement, an unstable security situation and widespread corruption — kin is the sole depository of trust. The owner of a transport company indeed seemed puzzled by the relevance of our question, as to whether his business collaborators in Afghanistan were relatives. He thus answered: “If they’re not relatives, who are you going to trust?”

Linkages to the Shadow and War Economy

Jonathan Goodhand has discussed how the opium culture in Afghanistan cannot be simplistically treated as a mere criminal activity, demonstrating that in the current politico-legal void in Afghanistan, it sat at the intersection of combat, shadow and coping economies.[17] Opium is however only one such commodity in this thriving cross-border market, in which formal trade seamlessly overlaps with smuggling and drug traffic and finally, finds inroads into the war economy.[18]

Edwina Thompson, has demonstrated substantial linkages between the hawalah system and drug trade in Afghanistan, the former frequently serving as a money laundering channel to the latter. In this complex traffic, Peshawar acts as an access point to the formal international market system as well as to international clients of Afghan drug dealers.[19] Access to these markets is vital for supplies in fresh currency, as well as for legal investment opportunities, for example commodity imports into Afghanistan.[20]

The 1959 Afghan Transit Trade Agreement allows Afghanistan access to the Karachi seaport for the transit of its own import, without having to pay any intermediary duty to Pakistan. However, of the totality of goods imported into Afghanistan through transit trade, the bulk does not reach the markets of Kabul, but are rather stopped at Jalalabad and redirected to Pakistan through alternative roads, in particular to Peshawar’s notorious Karkhano market.

Afghan and Pakistani traders have since long found the relative strength and weaknesses of each national market, and managed to combine them. While the price of imported commodities is substantially lower in Afghanistan due to the absence of taxes, its market size is limited. Conversely Pakistan offers a sizable market, but has a stringent tax regime, remnant of old Import Substituting Industry policies that makes import prices exorbitant. Thus, traders combine the best of both worlds by ordering several times the amount of goods they need to import to Afghanistan, avoiding Pakistan’s taxes according to the ATTA, and resell most of it in Peshawar or elsewhere in Pakistan at prices higher than Afghanistan’s, yet still cheaper than they would be on the legal market in Pakistan.[21]

Black market trade has contributed to create an industry of its own, with high levels of integration at the top — between the traders importing from abroad or exporting directly from Pakistan to Afghanistan, and the mainly Afridi and Shinwari smugglers, who carry back the goods into Pakistan through alternative routes — and a fragmenting traffic at the bottom, breaking down into individual carriers employing diverse modes of transportation, and smaller client shopkeepers across the country.[22] In the meantime, counting for a fraction only of the overall value of this traffic, it appears as if the whole (legal) Afghan Transit Trade is entirely financed through cross-border smuggling to Pakistan, which largely pays for what really gets imported in Afghanistan, and may artificially boost the supply capacity and “dope” the weak Afghan market.

Connections between formal trade, smuggling and drug traffic, inevitably lead up to the question of conflict economy. Although drug trade and smuggling both predate the Afghan conflicts, these trades have soon come under control, or at least tutelage, of warlords. Back in 1999, the Taliban, in whose controlled territory 97 percent of all Afghan poppy was grown at the time, are said to have raised US$45 millions in ushr and zakat over its cultivation[23]. But the Taliban, who later banned opium and poppy cultivation in 2001, derived most of their revenue from taxing ATTA smuggling, from which they are told to have raised US$75 millions in 1997.[24] In the current post-Taliban period, local power holders still collect important revenues from trade. Some transporters even complained that the situation had reverted to near pre-Taliban state, when check-posts, passage taxes and attacks on convoys were plaguing the country. In 2002, following the assassination of Vice President Abdul Qadir, inter-faction violence took place in Ningarhar over the control of trade routes.

Observations

There is a clear strategy on part of the Afghans settled in Pakistan which consists of exploiting their position as cross-border actors, a tactic which is also characteristic of the tribal people of FATA. As demonstrated by patterns of organization in the transport industry and cross-border trade, identity and marginality serve these borderland people in choosing conveniently between one market and the other, between one identity and the other to maximize profit, security of shelter, livelihood and access to capital, while minimizing transaction cost. In other words, by setting their headquarters within Pakistan, hawaladars, or traders, for example, make profit from more accessibility to world markets, to currency, and from the stability offered by a stronger formal financial system notwithstanding the non-negligible physical security offered by Pakistan’s relative political stability. Similarly, transporters will enjoy their position closer to supply markets, declaring their assets in Afghanistan to avoid taxation, and thus provide a service of greater quality at lesser cost. With a greater and more stable demand, Pakistan also offers a more attractive market for Afghan traders and transport that allows them to supplement for the deficiencies of the Afghan one, constantly in prey to the country’s political instability and the shadow of humanitarian disaster. However, armed groups also know and exploit these networks and strategies to their own end, feeding a vicious cycle in which the prospects of any stabilization through progressive normalization and (who knows?) formalization of the trade with Afghan is made more elusive.

The Borderland in Question and the Afghan Presence in Peshawar

Historically, it appears that regionalization and transnationalism has been both the problem and the solution in Afghanistan. Governance in Afghanistan has never been properly established with individualized citizenship conditioned to the supreme rule of the law, but was historically affected through nodal relations between self- (or foreign) appointed rulers and collective units (qawm, tribe, clan), bargaining terms of punctual alliances rather than recognition of law and authority. The borderlands of Afghanistan are extreme cases of state power being circumscribed by local political forces.[25] The never-ending power bargaining between Kabul and the Pashtun nomads has traditionally seen the “shifting (…) balance of power back and forth between core and periphery.”[26] However, the marking of the border in the midst of a territory inhabited by people refractory to state control, and its sharing between two weak and mutually hostile states has considerably pulled back this balance in favor of the periphery.

The anti-Soviet Jihad consisted precisely of arming, training and organizing the periphery against the core, endowing it with unprecedented power. The emergence of a Hazara power is another such manifestation of marginal turned disproportionately powerful relatively to the center, deriving their strength not only from foreign aid, but also from an increasingly criminalized economy. The American invasion in 2001 was in some sort that same scenario replayed, with local warlords given the balance of power, despite pledges of working at consolidating the state.

The situation of the Afghans staying in Pakistan is complex and contradictory. As the crisis prolongs in Afghanistan, their status as refugee (legal or de-facto), which should be understood as exceptional and temporary, becomes itself their long-term assurance to stability. Their position in Pakistan however, has somehow positive effects on Afghanistan too. By exploiting their position as cross-border agents, Afghans in Peshawar have, of course, subverted the border to suit their own ends and avoid constraints, but have also provided stable and secure bases for capital accumulation, indeed providing returns to the Afghan market: through the opening of a company branch in Afghanistan, through boosting weak local markets from bases acquired on stronger ones (albeit at the expense of the latter); or through foreign remittances, allowing the maintenance of landed assets which provide long term gains not otherwise achievable.

Yet the transnational network paradigm is somewhat a double-bladed sword. Because the few profitable inroads available heavily overlap with illegal or informal trades, as we have seen with smuggling and opium trade, Afghan expatriate businesses do also cave in to the strategies of local power holders in the borderland. Indeed, through elaborating strategies to address their problem of uncertainty and prolonged situation as refugee, Afghan cross-border entrepreneurs also contribute, directly or indirectly, to maintain this instability, by providing high profit opportunities to parties with their own power designs, inimical to objectives of stabilization and state consolidation and ultimately formalization of social and economic institutions.

Towards Sustainable Policy

The sole weight of the refugee phenomenon is such that no scheme for durable resolution of Afghanistan’s deep structural crisis can go without counting them in. In the same way, for Pakistan, there is no solution to its Afghan refugee problem other than a durable resolution to Afghanistan’s current state of collapse. This process, however, is nowhere near conclusion. The international community must at last reorient its approach towards a long term sustainable policy. Based on in-depth research in Pakistan, AREU came up with similar conclusions that the traditional refugee-relief paradigm was not anymore suited to respond to Afghan refugee’s complex situation. They argued in favor of an approach that would consider Afghans’ mobility and transnational strategies.[27] UNHCR has recently taken steps in that direction too, opting for a mid- or long-term “developmentalist” strategy in developing programs to support cross-border networking and foster economic linkages to strengthen communities across the border.

The Transnational Approach: Current Problems and Glimpses of Solutions

However, as Nasreen Ghufran accurately remarks, the proposed “transnational framework” comes in outright contradiction with the principle of refugee status, rather reframing Afghans as a diaspora, with an emphasis on economic motivations, instead of security.[28] Secondly as she puts it, it implies that Pakistan, despite its own overwhelming poverty issue, should be ready to accept the presence of Afghan refugees indefinitely, an idea which is most hypocritical on the part of the so-called international community, given the West’s own hysterical hardening towards asylum seekers at its gates. What this denotes indeed is the emptiness of a concept, which, while being an acute sociological observation leading to much reflection concerning appropriate sustainable approaches to a protracted refugee situation, does not make a policy as such.

Another issue is that AREU’s approach tends to be evangelical about the nature and potential of Afghan’s transnational networks. As it has been long proven and I have reminded it in this paper, Afghans’ cross-border trade and transport networks extensively overlap with the illicit and the bellicose.

Nevertheless, at present time, repatriation shows just as problematic. In Afghanistan at the moment, a deteriorating security situation goes hand in hand with a bitter failure on the economic front. The apparent successes, in numerical terms of the 2002-2006 repatriation effort was met with mitigated results in rehabilitation. Afghan refugees returned to the country in a worse-off position than they were before, in the midst of increasing internal displacement and faltering efforts from international community at holding to its promise of reconstruction.[29]

Thus, transnationalism for its own sake will not make a policy. However, it is a historical reality — and a powerful economic strategy — of the borderland that cannot be denied a look when designing strategies. The Afghan cross-border trade and transport are indeed formidable networks that can potentially be harnessed as a growth locomotive for the economic rehabilitation of Afghanistan. Of course, in the meantime the situation of refugees in Pakistan does not change with acknowledging this fact. Cross-border networking can be a model on which to draw viable self-help projects, but refugee relief will still demand steadfast support from international actors. Another challenge will be to rethink the two countries’ trade regulations and harmonizing them, thus striking a balance between the two and deterring smuggling. At the same time, regional policies regulating transport and trade, including currency trade, which would involve national banks and the state could allow the sector to flourish in a way favorable to the reconstruction of Afghanistan as well as to Pakistan’s own development effort. The only way to make repatriation a sustainable solution to the refugee problem is by working to solve these deep-seated issues that create the refugee flows in the first place. This means of course colossal effort on part of the international community to bring adequate aid and investment into Afghanistan to pursue the reconstruction effectively. At last we need a sustained, long-term plan to support Pakistan as a state, which bears alone, with Iran, the quasi totality of Afghanistan’s near-5 million refugees. The Western powers, so prompt at telling Pakistan how it should act toward refugees, should face their own responsibilities in this matter.

References

Collective for Social Science Research. 2006, January. Afghans in Peshawar: Migration, Settlements and Social Networks. Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) Case Study Series.

Thompson, Edwina. 2005. The Nexus of Drug Trafficking and Hawala in Afghanistan. UNODC Draft Report.

UNHCR and the Ministry of States and Frontier Regions of Pakistan (SAFRON). 2005. Census of Afghans in Pakistan.

Rubin, Barnett R. 2002. The Fragmentation of Afghanistan: State Formation and Collapse in the International System. Second Edition. Yale University Press.

Rasanayagam, Angelo. 2005. Afghanistan: A Modern History. London: I. B. Tauris.

Baud, Michael. and Willem van Schendel. 1997. “Toward a Comparative History of Borderlands.” Journal of World History. Vol. 8 (No. 2).

Goodhand, Jonathan. 2005, April. “Frontiers and Wars: The Opium Economy in Afghanistan.” Journal of Agrarian Change. Vol. 5 (No. 2).

Edwards, David Busby. 1986. “Marginality and Migration: Cultural Dimension of the Afghan Refugee Problem.” International Migration Review, Vol. 20 (No. 2, Special Issue: “Refugees: Issues and Directions,” Summer).

Ghufran, Nasreen. 2006. “Afghan Refugees in Pakistan Current Situation and Future Scenario.” Policy Perspectives. Vol. 3 (No. 2, July-December).

Korf, Benedikt. 2005. “Participatory Development and Violent Conflict – An Antagonism?” International Journal of Rural Management. Vol. 1 (No. 1)

Monsutti, Alessandro. 2004, June. “Cooperation, Remittances, and Kinship among the Hazaras.” Iranian Studies. Vol. 37 (No. 2).

Rubin, Barnett R. 2000. “The Political Economy of War and Peace in Afghanistan.” World Development. Vol. 28 (No. 10)

Related Sources

Hussein, Waqar. 2004. The Effect of the ATTA on NWFP. Thesis submitted as final requirement for the degree of doctorate of philosophy (PhD) in Area Studies (Central Asia) of the University of Peshawar. With the special permission of the Head of the Area Study Center (Russia, China & Central Asia), University of Peshawar, Peshawar, Pakistan.

Jazayery, Leila. 2002. “The Migration-Development Nexus: Afghanistan Case Study.” International Migration. Vol. 40 (5).

Rubin, Barnett R. 2006, September 1. “Afghanistan’s Geo-Strategic Identity.” Lecture for the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Philadelphia, PA. With permission from Professor Barnett R. Rubin.

Lister, Sarah and Adam Pain. 2004, June. Trading in Power: The Politics of “Free” Markets in Afghanistan. AREU Briefing Paper.

Turton, David and Peter Madsen. 2002, December. Taking refugees for a ride: The politics of refugee return to Afghanistan. AREU, ECHO.

White, Philip and Lionel Cliffe. 2004. “Matching Response to Context in Complex Political Emergencies : ‘Relief’, ‘Peace-building’ or Something In-between?” Disaster. 24(4).

[1] For the realization of this work, I wish to address my sincerest thanks to the Faculty of Law and Social Sciences of the School of Oriental and African Studies (University of London); Jonathan Goodhand, Senior Lecturer in Development Studies at the Faculty of Law and Social Sciences at SOAS; Mrs. Fozia Tanveer; Mr. Paolo Novak; SPO-Peshawar and SPO-Islamabad; Mr. Naseer A. Nawidy and Mr. Sheharyar Khan of the Institute of Policy Studies, Islamabad; Dr. Nasreen Ghufran of the International Relations Department at the University of Peshawar; Dr. Sarfraz Khan of the Area Study Center, University of Peshawar; Dr. Azmat Hayat Khan, Director of the Area Study Center of the University of Peshawar; Munazza Hadi of UNHCR; Dr. Ahmad Noor; Mr. Jehan Derwaiz Khan; Mr. Afrasiab Khattak; and Mr. Aimal Khan of the Sustainable Development Policy Institute.

[2] UNHCR and SAFRON, 2005, p. 5–7.